Guest article: The brain – the center of our performance II

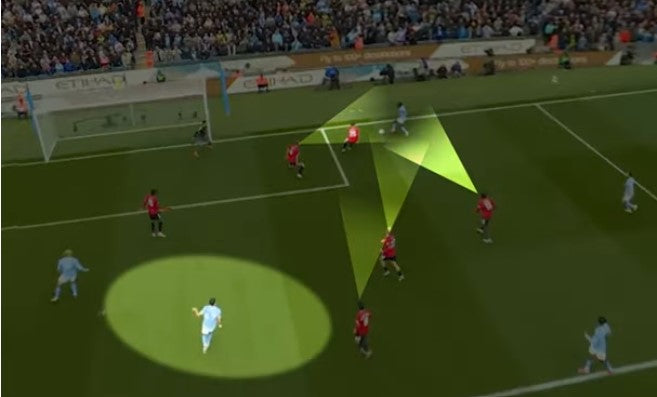

The last post concluded with the question of which solution is the right one in the following situation:

Fictional game situation: Ball capture in the center by “red” after play build-up by “white”.

- Option: He decides to dribble into the open space

- Option: He decides to pass to the starting winger

- Option: He decides to play a deep pass to the striker between the IV`s

Which is the right solution?

Correct! The one that leads to the gate. And there is no one solution for that.

The player makes his decision based primarily on experiences he has had in similar situations in the past. If the outcome was positive, he will prefer to look for this solution again. If the outcome is negative, a new strategy is developed.

Let us now consider a negative and a positive outcome for option 2:

Positive outcome: Striker runs alone towards the goal -> positive evaluation of the solution

Negative outcome: Opposing IV is strong in positioning and intercepts the pass

- Maybe dribbling around a central defender or passing to the winger would have been a better option?

When does my player act consciously, when unconsciously – and which is better?

If a player makes many decisions unconsciously, i.e. INTUITIVELY correctly, he needs significantly less time to make his decision, as the brain processes stimuli more quickly. In this context, people also like to talk about PLAYERS who act more quickly. However, the more complex the game situation becomes, the more difficult it is to make the right decision unconsciously. More experienced players already have an AUTOMATED SUCCESSFUL ACTION STRATEGY, even in increasingly complex game situations.

So does the player in our example make the decision unconsciously or consciously?

Correct! Of course, that depends on the individual player. If our player is an inexperienced youth player, he needs more time (remember: more fixations, less information per fixation, longer conscious decision-making) for his action process.

We therefore need to get our players to PERCEIVE the situation CORRECTLY by "scanning" the game-deciding scenes with their FIRST LOOK and peripherally perceiving the events around them. Even in increasingly complex situations, they should make a DECISION with a SUCCESSFUL OUTCOME as automatically as possible without long thought processes and also IMPLEMENT this motorically PERFECTLY.

But how do we do that?

Stop dictating actions to players

In football, tactics are often understood as instructions from the coach to the players about how they should behave. When we talk about TACTICAL KNOWLEDGE, this is absolutely correct. This includes, for example, the EXPLICIT COMMUNICATION of game systems, the benefits of certain actions (“if-then strategies”) and behavior in standard situations.

However, the more complex and open the game situation, the more important IMPLICIT LEARNING becomes for our players. Only through this unconscious processing of information can AUTOMATISMS arise that enable players to act unconsciously and therefore very FAST. A study by Berry & Broadbent (1984) even showed that explicit knowledge often has a negative effect on performance.

Mistakes are essential

As we now know, youth players in particular MUST make MISTAKES. Only then can they develop differentiated action plans in different situations and have the opportunity to choose the right one from a SERIES OF ALTERNATIVES (illustrated graphically in Figure 3). To do this, we coaches must continually present the players with new challenges through suitable training content. The way we coaches deal with the players is particularly important. We must make it clear to them that it is not a problem if something doesn't work out.

Fig. 3: Coupling of situation and action: selection of action from alternatives (according to Roth).

Breaking patterns and making players variable

To do this, let's go back to our example: Our player INTUITIVELY chooses option 1 and dribbles because he is fast and often solves situations successfully. However, he increasingly loses sight of the free player in the depth.

If dribbling is his strength, then we as coaches must not under any circumstances deprive him of it. Our job is to help him to use this strength correctly. To do this, we must teach him what HE needs to pay attention to in order to recognise whether another option might be more likely to be successful.

Getting players to use their own brains

In football, as everywhere, there is rarely just one solution. When choosing a solution, it is important that the player sees a plan behind it, which he develops INDEPENDENTLY. We achieve this through suitable game forms in which the players are constantly faced with new tasks. Simply asking the question after a failed action "what would have been a possible better solution" helps the player to reflect on himself.

Correctly assess the reason for failure

A player has an outstanding idea, but fails to implement it in his motor skills. Should we criticize our player for this? No, quite the opposite! "Very good idea!" is our feedback and the player's technical skills must be worked on. Because if he can then successfully implement his game-intelligent thoughts in motor skills, we as coaches have done a lot right.

Tobias Bierschneider (24) lives in Leipzig. Current graduate of the master's course "Diagnostics and Intervention in Competitive Sports". He is an assistant coach for the U11 team of RB Leipzig. Before that, he lived in Munich for 5 years, where he completed his bachelor's degree in "Sports Science" at the TU. In the 2017/18 season, he worked as an assistant coach for the U14 team of SpVgg Unterhaching. He gained his first experience in a NLZ in 2016 as part of an internship at FC Ingolstadt.

Sources

- De Groot, A. (1969). Perception and memory in chess; an experimental study of the heuristics of the professional eye. Mimeograph; Psychological Laboratory University of Amsterdam, Seminar September.

- Gralla, V. (2007). Peripheral vision in sport. Possibilities and limitations illustrated using the example of synchronoptical perception. Bochum (also dissertation Ruhr University Bochum Faculty of Sports Science)

- Helsen, WF, Pauwels, JMVisual search in solving tactical game problems. In: Daugs, R., Mech-Ling, H., Blischke, K., Oliver, N. (eds.): Sports motor learning and technical training. Volume 2. International Symposium “Motor Skills and Movement Research” 1989 in Saarbrücken. Cologne 1991, 199-202

- Hohmann, A., Lames, M., Letzelter, M. (2014). Introduction to training science (6th edition). Wiebelsheim: Limpert

- Rösler, F. (2011). Psychophysiology of cognition. Introduction to cognitive neuroscience. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag

- Taylor, St. (1965). Eye Movements in Reading: Facts and Fallacies. American Educational Research Association, 2 (4), 187-202.

- Williams, AM, Davids, K. (1998). Visual search strategy, selective attention and expertise in soccer. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 69 2, 111-128

Author: Tammo Neubauer