Leadership and team development in football

For most Bundesliga football clubs, the transfer carousel turns at an impressive speed in the summer. But many lower-class teams are also reassembling their squads for the upcoming season. In team sports, the team begins to develop in this phase. This process is long-lasting and should be observed and controlled by the coach from the very beginning. This editorial, "On leadership and team development in football," provides important sports psychology standards and offers helpful tips for everyday training.

Dr. René Paasch reports for RESWITCH :

Football is a team sport - despite all the individualists. That is why the topic of team development is a key tool for every coach in every league to develop performance-enhancing measures. Joachim Löw, coach of the German national football team, said the following in an interview: "Respectful, trusting cooperation in our team is very important to me; reliability and trust are key factors in this context. Open communication at eye level, the ability to accept criticism, transparency and tolerance - we have set an example for this, but it takes a while for something like this to be internalized by everyone, the players and the coaches. Until everyone trusts each other" (see Zeit, May 31, 2012). It is precisely in this core statement by Joachim Löw that the extensive processes of continuous and time-based team development and leadership lie.

Group cohesion/team cohesion

Before I go into the phases of team development according to Tuckmann and Lau, I would like to offer you the term group cohesion or team cohesion, as this is very important in a sporting context. Cohesion is derived from the Latin verb "cohaerere", which means to be connected to one another. Terms such as cohesion, team spirit or group morale are often used synonymously. In sports psychology, the theoretical model of group cohesion by Albert Carron and colleagues (Brawley and Widmeyer, 1998) is usually used. According to the model, group cohesion can be divided into four different factors. Firstly, a distinction can be made between task-related and social cohesion . Secondly, the group is viewed as a whole and the individual in the context of the group . The difference between the last two aspects can be illustrated with an example: You might have a team in which 15 of the 16 team members do a lot together. One athlete, on the other hand, is left out. If you ask this athlete about the unity of the group, he would have to say that it is high, because this is also true for the group as a whole. However, the athlete himself is not integrated into it and therefore his connection to the group is low. From the findings so far, the following can be hypothetically concluded: teams that rate their task cohesion higher than other teams also tend to be more successful. Successes and failures over the course of the season do not necessarily lead to changes in the perception of cohesion within the team. It is more likely to be possible to demonstrate a higher, positive influence of previous sporting success on cohesion than the other way around (Lau, Stoll, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2007).

In the following text, I will show you the important starting points for development and continuous performance in a team. The term "team" is being talked about everywhere these days. But what exactly does it mean? The linguistic root of the term "team" comes from Old English and comes from the meanings "family" and "team". But what makes a family? We are connected to one another, we share a common name, we share common beliefs and values, we stick together. And the term "team" also creates a clear idea: we pull together and we use our strengths in the same place and for the same goal. In this context and as an introduction, the phase model by Tuckmann (1965, 1977) applies.

In the first phase, "Stage: Getting to know each other", the team members get to know each other. They explore whether they feel they belong to this group and, if so, what role they play in it. In this phase in particular, feelings of insecurity and cautious reserve arise, which require sensitive guidance from the coach. It is therefore advisable to focus on goals and clear guidelines. The coach should endeavour to find out about the motives and expectations of the athletes and try to align them with his ideas. In this phase, attention should be paid to creating a good atmosphere in order to strengthen the positive initial motivation. In the second phase, "Stage: Confrontation - Conflict phase", it is essential that the coach observes the formation of subgroups and intervenes if necessary if you want to be effective and successful in the long term, especially if the groups are too strong and dominant. Interpersonal conflicts, rebellion against the coach, resistance to group control or to group norms are normal behaviors and require careful guidance from outside. In this phase, the trainer has the task of identifying strengths and weaknesses, making them transparent and being able to assess them. The athlete should then know his task and role within the team. In the transition from the conflict phase to the "stage: consolidation", the trainer should carefully consider where to actively intervene and where to leave the process to the group. Consolidation should then be supplemented by solidarity and cooperative income. The next phase, "stage: performance", is where success comes. Team members gather their strength to achieve a common goal. There are always new paths in the process that lead back to an earlier phase, for example with new signings or new conflicts. Overall, the process should not be viewed one-sidedly, but from a holistic perspective. From this perspective, it becomes clear that there are basic rules that apply to all groups. Regardless of whether they are families, interest groups, clubs or even teams. These rules "apply tacitly" without them having been agreed upon. Observe familiar and successful teams. You will probably find some of what I describe below in your everyday sporting life.

Team development training

Another interesting concept of team development for sport is team development training (TET) by Lau (2005b). This integrative training combines the practical interaction between sports training, competition and the social development of the team. Furthermore, TET uses person- and group-centered measures that also include changes in organizational structures. TET is based on the following four basic assumptions:

1) The team is capable of development and learning;

2) The team communicates with its environment;

3) The performance optimization of the team has a central function and

4) Changes within the team are more likely to be accepted by the players when their needs and wishes are taken into account.

The objectives of the TET are therefore:

- Setting team goals

- Developing an understanding of the role of each team member

- Promoting communication

- Initiation of conflict management for factual and relationship problems

- Balance between cooperation and competition within the group

- Promoting awareness of interdependence within the team.

In the spirit of interdisciplinary and system-theoretical orientation in explaining collective performance in sport, Lau’s team development training (TET) is based on the following principles:

- Based on a training plan that follows the principle of cyclization and periodization.

- Focused on optimizing collective performance requirements.

- The team is a social system that separates itself from its environment but communicates and interacts with it.

- Corresponds with training and competition control measures.

- Primarily designed for the entire team, group and personal methods complement the available inventory of methods.

- Combines planned and situation-dependent intervention measures.

- Supports positive team development trends and specifically disrupts undesirable developments.

- Based on a systematic team diagnosis and requires competent intervention management.

It becomes clear that the TET is not based on a fixed sequence of phases of team development, as with Tuckmann, but is integrated into the structure and functions of sports training and competition with accompanying measures. In addition to recurring and standardized phases in the course of a football team's season, it is primarily group-specific, unforeseeable situations that are used as an opportunity for targeted intervention measures. The success of the TET therefore depends heavily on the trainer's leadership behavior. In concrete terms, the question is whether it is possible to promote this process through individual and collective measures?

Goals

"The common goals" of today are the present of tomorrow. Goals therefore extend from the present into the future. That is why goal setting is one of the most important motivational measures in a team. This gives clues as to how a team can be brought together when necessary. The common goal is always the starting point. Coaches should always convince their players of this at the beginning. And this goal can be referred back to again and again. And it is important that you not only have a common goal, but also depend on each other to achieve the goal. From my experience, I know that athletes often forget how dependent they are on their teammates. That is why I emphasize this aspect again and again. In my view, there are different types of goal setting, which differ in terms of their timing and their content. That is why it is important that the personal goals of the individual members are in the interest of the team goal. The "temporal goals" that extend into the future therefore change the concrete achievability and lead to targeted changes. “Short-term goals”, on the other hand, are a guide for long-term goals, as they tie these into a manageable time frame. “ Medium-term goals” motivate over a manageable period of time, e.g. over a period of four weeks to six months. The “long-term goals” as a guiding principle control the long-term goal, “short-term goals” and “medium-term goals” lead to forward-looking activities. The very general description of the different types results in the choice of goal and the different types of goals, such as “good intentions”, “result goals” and “ability goals” (physical-conditioning, coordination-technical, cognitive-tactical and mental goals). Despite all the good planning, coaches should bear in mind that only when athletes define their goals themselves or at least accept them do they take responsibility for them.

Regulate

"The common rules" are the cornerstone of a team. The team uses them to determine what is important to it and where it sees its limits. Fixed rules include concrete things like a list of penalties for using the telephone during team meetings. Such rules are important because they ensure that the team's processes function properly and offer orientation to individual athletes. The same applies to rules that are not always stated openly but are nevertheless effective. Coaches could, for example, ask what behavior is desired or undesirable on the field? Does the youngest player have to collect the bibs? All of these things say something about the team's self-image and what is important to them. Coaches should talk to their team about this before the season and be surprised by what comes out of it.

identity

“The common identity” : In business, it has long been standard practice to develop an internal company mission statement. This describes who you are and/or want to be, what values you represent and where you see your own tasks and strengths. Such a mission statement is also helpful in sport, because it makes it easier for the individual to identify with the whole. References:

- I am proud and happy to play in this team.

- We will play confidently in our game and stand up for each other.

- For our team, we play with strength and with constant commitment, come what may!

- And so we will be a team and play successfully!!!

Unfortunately, such visions and images are used far too rarely. Yet they are so obvious. For example, is there an animal in the club's crest? Let's think of ice hockey. The Berlin Eisbären. These are very clear symbols. But even without an animal symbol, there are many ways to create guiding principles. Let's start, for example, by having you as a coach sit down with your team in a relaxed setting before the start of the season and talk about your dreams and your sport-related ideals. And then put together how the individual players see themselves:

- What are our strengths and how do we work together on our weaknesses?

- What is characteristic of your team?

- What values do they stand for?

The coach then brings the ideal and the reality together. The mission statement should point to the future. Formulate the essence of this mission statement in a concise symbol (S04 in football: The blue and white love) or sentence (e.g. "We are successful footballers with heart and hand."). This symbol, this slogan can accompany you in the coming months. It can even be passed on to the youth teams, so that a synergy effect arises. With the common goal, the common rules and the common vision, you have a good basis that brings your team, the club and possibly the fans together and that can accompany you in a helpful way throughout the entire season. I would like to give you a current example from the film "The Team". It is a film that bears the signature of national team manager Oliver Bierhoff. But it is certainly also a contribution from team psychologist Hans-Dieter Hermann. It is no coincidence that Bierhoff keeps appearing and intervening in interviews and that the public is increasingly reporting on applied sports psychology in football, especially on Hermann. Thus, the Campo Bahia and the team spirit are the key to winning the World Cup. The two points vary again and again over the 90 minutes and show the impressive face of a real team. In my view, the key statements are as follows:

BRAZIL HAS NEYMAR

QUOTED BY STEVEN GERRARD ,

ARGENTINA HAS MESSI

PORTUGAL HAS RONALDO

GERMANY HAS A TEAM

https://youtu.be/MaBDSzWusWo

Communication and leadership

In my experience, "communication" is the most frequently used keyword, alongside leadership. Where athletes and coaches interact, interaction and exchange play a central role. In communication, therefore, statements always have a factual and a relational aspect. In addition to pure information, each team member always shares something "from themselves" with whom he or she is related. The way the team communicates with each other shows a sports psychologist how the relationships between athletes and coaches are. Communication in a team typically runs like a restless mood curve. At first, the mood is good and optimistic, until the first arguments arise. Only when these are resolved can things continue productively with a good feeling. I will now show you what I believe is the ideal way of communicating, which makes a team more successful:

- Respectful and appreciative attitude towards teammates

- Active listening and follow-up

- Address mistakes openly and respond to them in a solution-oriented manner

- Send I-messages

- Communicating through the five senses

- Limit content to the essentials

- In the competition, choose simple content and send it in a targeted manner

There is no button for successful communication. It is not enough to make it clear to the athletes that you expect them to communicate in a positive way without living it yourself. None of the above points work just like that. Effective communication is the result of constant work on the team and feedback on your own communication style.

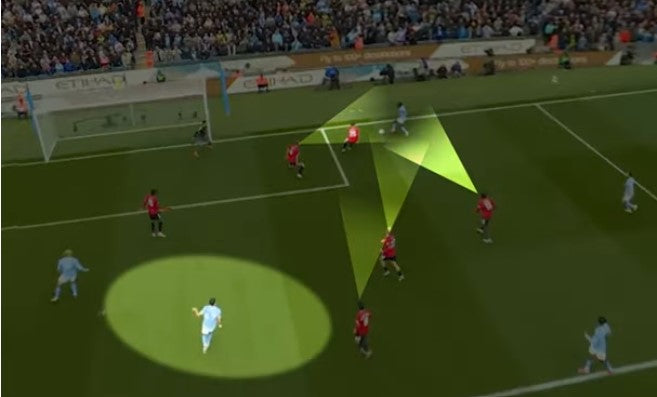

Task and scooter distribution

Getting to know the individual and collective distribution of tasks and roles and knowing their strengths and special features increases the inner security of a growing team. The playing position and the associated roles are particularly worth mentioning here. The playing position indicates the place that the individual occupies in the team. It is important that this position remains interchangeable, but equally not every team member is able to fulfil the tasks associated with this position. The associated function is then referred to as a role. The role is in turn the expectation that a player should fulfil in a position. There are two aspects linked to this: the demands and duties that are tied to the role and the personal contribution to the team's performance. The understanding of the role therefore includes the following questions for the athlete:

- What do I have to do? (mandatory)

- What can I do? (Degree of individuality)

- What should I do? (personal expectation)

- What can I do? (Self-assessment) (Baumann, 2002)

Every player must therefore first fulfil the requirements and duties. By being aware of this, the athlete can use his personal skills in a targeted manner. It should not be forgotten that there are complex roles that require variable behaviour, such as the central midfield position. Therefore, early knowledge of the position and role in the team is another component of a real team.

If we now look at the list of the components of a real team mentioned above again and go back to our example situation with you as a coach: Where do processes need to be developed in your current team or in the planned seasonal preparation? And which points do you have the most experience with as a coach? Are you, for example, able to develop this complexity of a team? Only if you yourself manage to get the components mentioned under sufficient control and lead them sensitively from the outside will you be able to create the appropriate team spirit and the appropriate result in your team.

Summary

In summary, it can be said that the phases of team development take place continuously and require sensitive leadership. The common goal, the common rules and the common vision are a very good basis for bringing the team together and supporting them in a helpful way, seasonally. Just like everyday communication and dealing with the distribution of tasks and roles, these points influence the development process of a team. Last but not least, I would like to warmly recommend the documentary film “Trainer”! Aljoscha Pause provides real insights into the everyday work of a football coach. Team meetings and realistic images as well as many personal assessments paint an interesting picture of the coach, who is constantly under extreme psychological pressure from the public.

You can find a small excerpt in the following trailer:

Conclusion: In developing and strengthening a real team and in providing trustworthy support, sports psychologists can provide effective support in conjunction with the coach, the functional team and those responsible. In my opinion, the complexity of these processes makes it essential that sports psychologists become an integral part of the coaching staffs of Bundesliga football clubs.

literature

Carron, AV, Hausenblas, HA & Eys, MA (2005). Group dynamics in sport. Morgantown: Fitness Information Technology.

Carron, AV, Colman, MM, Wheeler, J. & Stevens, D. (2002). Cohesion and performance in sports: A meta-analysis. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 24, 168-188.

Carron, AV, Brawley, LR, & Widmeyer, WN (1998). The measurement of cohesiveness

in sports groups. In JL Duda (Ed.), Advances in sport and exercise psychology measurement

(pp. 213–226). Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology.

Carron, AV, Widmeyer, WN & Brawley, LR (1985). The development of an instrument to assess cohesion in sport teams: the Group Environment Questionnaire. Journal of Sport Psychology, 7, 244-266.

Argyle, M. (2005). Body language and communication. The handbook of nonverbal

Communication. 9th ed. Paderborn: Junfermann.

Baumann, S. (2002): Team psychology: methods and techniques. Aachen: Meyer & Meyer.

Ulrich Voigt, Martin Christ and Jens Gronheid: The film “The Team”

Eberspächer, H. (1982): Interaction processes and groups in sport. In Eberspächer, H.: Sport psychology. Reinbek: Rowohlt. Pp.197-242.

Esser, A. (2005). On sport psychological work with the women’s national team

Hockey. In G. Neumann (ed.), Sports psychological support for the German Olympic team 2004. Experience reports – success stories – perspectives.

Hübler, A. (2001). The concept of 'body' in linguistics and communication sciences. Stuttgart: UTB.

Jackson, P. (1995): Sacred hoops. New York: Hyperion.

Kauffeld, S. (2001): Team diagnosis. Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Krueger, R. (2001): Teamlife: From Defeat to Success. Wirtschaftsverlag Carl Ueberreuter.

Lau, A. & Stoll, O. (2002). Validity and reliability of the questionnaire on team cohesion in sports teams (MAKO-02). In S. Schulz (ed.), Report on the 43rd Congress of the German Society for Psychology in Berlin (p. 374). Lengerich: Papst Science Publishers.

Lau, A., Stoll, O. & Hoffmann, A. (2003). Diagnostics and stability of team cohesion in sports games. Leipziger sportwissenschaftliche Beiträge, 44 (2), 1-24.

Lau, A., Stoll, O. & Schneider, L. (2004). Development of a Questionnaire to Measure Cohesion in Team Sports . Conference Proceedings – Association for the Advancement of Applied Sport Psychology in Minneapolis/Minnesota (p. 66).

Lau, A. (2005a): Collective performance in sports games – an interdisciplinary analysis. Habilitation thesis. Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg.

Lau, A. (2005b): Team development training – a systemic concept for team sports. Leipzig Sports Science Contributions, 46(1), 64-82

Lau, A. & Stoll, O. (2007). Group cohesion in sport. Psychology in Austria, 27 (2), 155-163.

Ligget, DR (2004) Sports hypnosis. Heidelberg. Auer

Linz, L. (2003): Successful team coaching. Aachen: Meyer & Meyer.

Poggendorf, Armin / Spieler, Hubert (2003): Team dynamics – training, moderating and systematically setting up a team, Paderborn: Junfermann Verlag. (ISBN 3-87387-531-4)

Tuckman, Bruce W. / Jensen, Mary Ann (1977): Stages of small-group development revisited, Group Org. Studies 2.

Tuckman, Bruce W. (1965): Developmental sequence in small groups, Psychological Bulletin, 63, pp. 384-399.

See Zeit from 31 May 2012: Interview with Joachim Löw, coach of the German national football team.

See Zeit from 26.08.2013: Interview with Markus Wiese, coach of the national hockey team

Author: Dr. René Paasch